Studiourile de film au fost parte integrantă a industriilor de cinema ale fostei Europe comuniste. În anii 90, după prăbușirea regimurilor din regiune, unele dintre aceste studiouri au fost privatizate iar altele au intrat în declin, pendulind vreme de decenii între supraviețuire și colaps, ca metafore materiale ale transformărilor specatuloase care care au afectat țările din regiune.

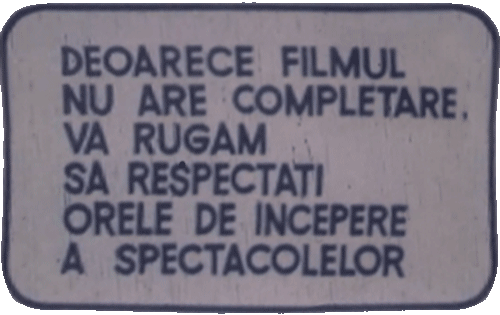

Alexandru Sahia” a fost studioul de cinema documentar al României socialiste. Înființat la începutul anilor 50, prin transformarea societății de stat Romfilm, studioul a documentat vreme de patru decenii viața cotidiană în România și evoluția regimului comunist, conform indicațiilor și în limitele impuse de mandatul politic al instituției.

Film studios, as institutions, were part and parcel of the cinema industries of former communist Europe. In the ‘90s, some of these studios were privatized while others began to decline, teetering for decades between survival and demise, as lasting material metaphors of the spectacular transformations taking place in the countries of the region after the collapse of the communist regimes that established them.

“Alexandru Sahia” was the documentary film studio of socialist Romania. Established at the beginning of the 1950s through a conversion of the “Romfilm” state agency, the studio documented daily life and the evolution of the communist regime over the course of four decades, according to the directives and the boundaries imposed by the institution’s political mandate.

Pentru că a fost singurul studio specializat în film documentar din epocă, instituţia s-a identificat în timp cu practica documentară la nivel național: astăzi, istoria documentarului produs în România socialistă este, cu câteva excepții, istoria documentarului Sahia. La trei decenii de la colapsul regimului Ceaușescu, studioul Sahia nu și-a găsit încă locul în prezent.

Its decades-long existence as the country’s only documentary studio led to the institution becoming synonymous with documentary practice: today, the history of documentary in Socialist Romania is, with few exceptions, the history of the documentaries produced by this studio. Three decades since the collapse of the Ceaușescu regime, the Sahia studio has yet to find its place in the present.

Planul tematic al studioului “Alexandru Sahia” anul 1989

Planul tematic al studioului “Alexandru Sahia” anul 1989

Colectivul studioului cinematografic ‘Alexandru Sahia’ a alcătuit Planul tematic pe anul 1989 în lumina sarcinilor ce revin cinematografiei româneşti din hotărîrile şi documentele Congresului al XIII-lea şi Conferinţei Naţionale a PCR, din orientările şi indicaţiile concrete ale Secretarului General al PCR, tovarăşul Nicolae Ceauşescu, formulate în expunerea făcută în Şedinţa Comitetului Politic Executiv al CC al PCR din 19.04.1988 şi în cuvîntarea din acelaşi for de partid din 6.05.1988. Aşezînd la temelia activităţilor noastre, ca sursă de inspiraţie majoră, indicaţiile Secretarului general Nicolae Ceauşescu, sarcinile reieşite din documentele de Partid, munca şi viaţa celor care edifică socialismul şi comunismul în patria română, cineaştii, realizatorii de film documentar şi ştiinţific depun toate eforturile pentru a contribui la promovarea spiritului revoluţionar prin opere cinematografice de o calitate ideologică şi cinematografică ridicată.

Thematic Plan of the Alexandru Sahia Studio, 1989

Thematic Plan of the Alexandru Sahia Studio, 1989

The collective of the ‘Alexandru Sahia’ Studio has drafted its yearly Thematic Plan for the year 1989 in the light of the responsibilities allocated to Romanian cinema through the Documents and Decisions of the Thirteenth Congress and the National Conference of the R.C.P., from the directions and clear guidelines provided by the General Secretary of the R.C.P., comrade Nicolae Ceausescu, as formulated in his speech at the Meeting of the Executive Political Committee of the R.C.O. on 19 April 1988 and in his speech to the same organization on 6 May 1989. By basing our entire activity on the precious guidelines provided by our General Secretary Nicolae Ceausescu, on the tasks laid out for us in Party Documents, as our crucial sources of inspiration, and by taking the works and lives of those who build socialism and communism in our Motherland as our main inspiration, we documentary filmmakers place our entire efforts towards contributing to the promotion of the revolutionary spirit in our country, through cinematic works of the highest ideological and aesthetic quality.

Înainte de finele regimului Ceaușescu, studioul de cinema documentar al Romaniei socialiste produce peste doua sute de filme de scurt-metraj pe an, croite pentru a se potrivi în categoriile prevăzute de Planuri tematice anuale precum cel de mai sus.

La nivel oficial, existența studioului e justificată de producția sa explicit politică: reportaje care documentează in extenso mobilitățile în teritoriu ale cuplului prezidențial, filme rutinier-triumfaliste sau „sinteze” produse în conjuncție cu aniversările politice ale zilei.

Over the course of the Ceaușescu regime, the studio produced over two hundred short films a year, tailored to fit the categories of the annual Thematic Plans.

Officially, the studio’s existence depended on its explicitly political production: newsreels covering the national and international travel of the presidential family or triumphalist works produced in response to the political anniversaries of the time. The thematic plan, however, left room for other types of non-fiction. These included the Weekly Newsreel (discontinued in March 1974), various forms of creative documentary, popular scientific film, and various other categories of films commissioned to the studio by other institutions of the socialist state, from the Bucharest Police Department to the National Tourism Office (ONT). Throughout its four decades of existence, the studio was regarded as an official mouthpiece of the regime, an institution directly involved in the social and political pedagogy practised by the socialist state. The image of Sahia was inextricably tied up with the image of political power. The documentarists were the main category of film professionals called upon to document the progress of communism through their immersion in a world undergoing profound transformation.

Astăzi, la treizeci de ani de la colapsul regimului Ceausescu, România nu mai are nevoie de Sahia pentru a-și documenta prezentul. Studioul nu mai produce film, iar de mai bine de un deceniu incoace e considerat „mort” – un mort paradoxal, asa cum a fost instituția însăși: deși în faliment, are încă două sedii atrăgătoare plasate în locații strategice (Bulevardul Aviatorilor, respectiv Strada Jean Louis Calderon), în mare parte închiriate unor instituții fără legatură cu industria de cinema.

Today, thirty years since the collapse of the Ceaușescu regime, Romania no longer needs Sahia to document its present. The studio no longer produces film and, for over a decade, it has been considered “dead”. However, this is a bit paradoxical, much like the institution itself: though bankrupt, the studio still has two attractive offices in central locations in Bucharest (Aviatorilor Blvd. and Jean Louis Calderon St.) which have mostly been rented out to institutions with no connection to the film industry.

Puține instituții românești au fost înconjurate de nostalgii precum cele acumulate în jurul studioului Alexandru Sahia în deceniile de dupa colapsul regimului Ceaușescu.

La începutul anilor 2000, Magda Mihailescu (critic de film) scrie despre „aura studioului Sahia din anii lui de glorie, văzut astăzi, din perspectiva timpului, ca un fel de Camelot al cinematografului nostru”.

În aceeași perioadă, regizorul Laurențiu Damian, angajat al studioului în anii 80, adăugă motto-ul „Et in Arcadia ego” unui capitol de volum in care își rememorează experiența personală în studio. (Filmul documentar: Despre documentar… încă ceva în plus, 2003).

În 2010, la aniversarea a 60 de ani de la înființarea studioului, regizoarea Tereza Barta, emigrată în Canada, scria în săptămînalul Dilema Veche: "Sahia, pentru mine, a însemnat copilărie şi tinereţe. A însemnat părinţii mei, prietenii mei, corcoduşul din faţa biroului tovarăşului director Moldovan, a însemnat ideal şi prietenie, şi iubiri, şi suferinţe, şi bucurii şi naşterea copiilor noştri, pentru că aveam grijă unii de copiii altora, şi ceaiurile de sâmbătă seara, şi schimburi din cele trebuincioase vieţii. Sahia a însemnat colectivitate şi suport, loialitate şi genererozitate. […] Oaza de umanitate pe care o port în mine se numeşte Sahia Film.”

Few Romanian institutions were shrouded in nostalgia the way the Alexandru Sahia Studio was in the decades following the collapse of the Ceaușescu regime.

At the beginning of the 2000s, film critic Magda Mihailescu wrote that “the aura of Sahia Studio in the glory years” in hindsight, looked like some sort of Camelot of Romanian cinema.

Around the same time, film-maker Laurențiu Damian, formerly an employee of the studio, added the motto “Et in Arcadia ego” to a chapter from a volume in which he recounted his personal experience at the studio.

In 2010, for the 60-year anniversary of the studio’s founding, film-maker Tereza Barta, since emigrated to Canada, wrote in a cultural weekly: “For me, Sahia was an essential part of my childhood and my youth. Today, I associate it with my parents [who also worked at Sahia] and my best friends, with the cherry plum in front of comrade Moldovan’s window, with all my youthful ideals, friendships, loves and anguishes, as well as with the birth of our children – because, as well as helping each other in other ways, we also cared for each other’s children. Sahia meant community, support, loyalty, and generosity. […] All these years, the memory of Sahia has been the oasis of humanity that I have cherished ever since.”

Emotionantă și, în același timp, parțială această memorie lansată în spaţiul public de cei afiliaţi cîndva studioului, în special după anul 2000, odată cu creșterea distanței dintre prezent și România socialistă.

În paralel cu ea, persistă încă, pentru cei de vîrstă matură, care vin cu experiența socialismului trăit, un bagaj memorial controversat atașat studioului – bagaj care începe chiar cu numele instituției. Cînd regimul socialist care înființează studioul decide să împrumute numele jurnalistului Alexandru Stănescu (1908-1937) – un scriitor devotat ideilor maxiste, mort la vîrstă de 29 de ani – pentru a denumi mai multe străzi și instituții ale României, printre care și studioul de film documentar proaspăt înființat, mai multe detalii sunt omise din biografia să oficială – inclusiv faptul că a adoptat pseudonimul ‘Sahia’ (din arabul „sahiya”–„adevăr”) în timpul unei călătorii în Orientul Mijlociu, după o perioadă petrecută la mănăstirea Cernica (perioadă în care, ironie, se pare că a aprofundat ideile marxiste).

This kind of moving, yet partial, memorialization of Sahia studio by those at one point affiliated with it appeared in the public space primarily after the year 2000, along with the growing distance between the present and the Socialist Romania of the past.

At the same time, for those with first-hand experience of that past, the memorial baggage attached to the studio still persists, incited even by its name. The studio’s secular godfather was a Romanian journalist (Alexandru Stănescu, 1908-1937) committed to the ideas of Marxism, who allegedly adopted the striking pen name ‘Sahia’ (stemming from the Arabic “sahiya”, meaning “truth”), during a trip to the Middle East, which followed a sojourn in an Orthodox Christian monastery. Yet these details were omitted from his official biography when the communist regime lent his name to hundreds of streets and institutions scattered across the country.

Patru decenii mai tîrziu, la doar cîteva luni după prăbușirea regimului Ceaușescu, un jurnalist (Bogdan Burileanu) notează într-un articol, parțial amuzat, parțial exasperat, că, paradoxal, România are un studio de documentar numit încă „Alexandru Sahia” al cărui sediu se află tot pe strada „Alexandru Sahia”.

În perioada următoare, doar strada își va modifica numele – în „Jean Louis Calderon”, după numele jurnalistului decedat acolo în decembrie 1989. Chiar dacă mai mulți angajați cer schimbarea titulaturii studioului – o mișcare necesară pentru înscrierea instituției într-o nouă ordine a istoriei – singura schimbare de nomenclatura va transformă, în 1991, „Alexandru Sahia” în „SahiaFilm S.A.”

Astfel, spre deosebire de studioul de film de ficțiune al României socialiste (București – „Buftea”), care a fost privatizat în 1998 – ironie, de un fost anagajat al studioului Sahia (Adrian Sîrbu) – devenind temporar „Studiourile MediaPro”, studioul de cinema documentar rămâne încă ancorat într-un trecut care supraviețuiește în numele „Sahia”.

Four decades later, just months after the collapse of the Ceaușescu regime, journalist Bogdan Burileanu noted in an article, half-joking, half-outraged, that, paradoxically, “Romania has a documentary studio still named Alexandru Sahia’ which is found on a street still named ‘Alexandru Sahia’.”

In the following years, only the street name was changed—to Jean Louis Calderon, after the journalist who died there in December 1989. Although quite a few of the employees requested the studio’s name be changed—a necessary decision for the institution’s transition to a new historical order—the only change occurred in 1991, from “Alexandru Sahia” to “SahiaFilm”.

Therefore, unlike the national fiction film studio (Bucharest – “Buftea”) which was privatized in 1998—by Adrian Sârbu, interestingly, a former employee of Sahia Studiu—and temporarily became “MediaPro Studios”, the documentary film studio still remains anchored to a perpetual past encrypted in the name “Sahia”.

Sahia a fost o instituție care a realizat filme produse pe banii statului dar poziționate împotriva statului.

Sahia n-a avut niciodată o conotație subversivă. Era un fel de univers paralel cu societatea socialistă a momentului.

Să nu uităm că Sahia a fost un instrument de propagandă...

Sahia i-a salvat pe mulți documentariști în timpul epocii de aur socialiste.

Sahia a fost una dintre acele instituții mici, izolate și profund subversive pe care sistemul le permitea ca supape de siguranță.

Sahia a fost o instituție-mamut caracterizată de o producție-mamut întreținută artificial de către statul socialist.

Sahia a fost pentru mulți o sinecură.

Pentru noi, Sahia a fost întotdeauna o familie...

Pentru mine, Sahia rămâne exemplul perfect de compromis politic.

Sahia was an institution which made films on the state’s money but against the state.

Sahia never had a subversive connotation. It was a kind of parallel universe to that of the socialist society of the time.

Let’s not forget that Sahia was a propaganda tool…

Sahia saved quite a few film-makers from starvation during the socialist golden age.

Sahia was one of those small, isolated, and profoundly subversive institutions which the system permitted as safety valves.

Sahia was a mammoth institution characterized by a mammoth production artificially maintained by the socialist state.

For many people Sahia was a cushy job.

For us, Sahia always felt like a family…

For me, Sahia is still the epitome of political compromise.

Cum a fost, de fapt, Sahia?

Și cum putem reconstitui viața și etosul

acestei instituții dincolo de un timeline

inevitabil simplificator?

What was Sahia really like? And how can we piece together the life and ethos of this institution?

Despre viața în studio, redactoarea Marion Ciobanu își amintește că „nu era tocmai neplăcută, doar că ni se arăta prea des pisica” – referire la o glumă care circula în spațiul estic în perioada respectivă, anume că cercetătorii sovietici care studiau în ce condiții șoarecii plasați în condiții de stress reușeau să supraviețuiască mai mult ajunseseră la concluzia că cei cărora li se arată mai des pisica mor primii.

La Sahia, „pisica” nu e numai inevitabilul aparat de cenzură, ci și proximitatea geografică a studioului față de epicentrul puterii politice: clădirea principală a studioului – din Bulevardul Aviatorilor 106 – e situată într-una dintre zonele exclusiviste ale Bucureștiului, populată de membri ai establishmentului politic trecut și actual. Unul dintre foștii vecini ai studioului în epoca e Ion-Gheorghe Maurer (președinte al Prezidiului Marii Adunări Naționale a R.P.R., 1958-1961; prim-ministru, 1961-1974,), care, la un moment dat, se și instalează într-una dintre clădirile vecine sediului central. Un alt moment reținut de mitologia apocrifă a studioului e cel al relocării urgente din Bulevardul Aviatorilor către un alt sediu – în strada… Alexandru Sahia (viitoarea stradă Jean Louis Calderon) – după ce câinele studioului latră prea înverșunat la Constantin Dăscălescu (membru în Consiliului de Stat al R.S.R., 1972-1975; prim-ministru, 1982-1989), aflat în vizită pentru proiecția unui film.

The anecdotal is often revealing of the “feel” of the studio: invited to recall her life at Sahia, former redactor Marion Ciobanu confessed that “it wasn’t that bad, really, just that we were shown the cat too often”. Her saying referenced a joke that circulated in Romania in the 1980s: when Soviet researchers decided to experiment to discover in what circumstances would rats live longer in confinement, they found out that those who were shown the cat the most often died first.

At Sahia, the “cat” was not only the censorship apparatus, as one may infer, but also the studio’s geographic proximity to political power: the main building of Sahia, from 106 Aviatorilor Boulevard, is situated in one of Bucharest’s most exclusive areas, populated by former and actual members of the political establishment as well as by the capital's nouveaux riches. One of Sahia’s neighbours was Ion Gheorghe Maurer, who had occupied a string of top positions in Romania’s government (president of the Great National Assembly Committee of the RPR, 1958-1961; Prime Minister, 1961-1974), and even moved into one of the studio’s buildings: the word goes that, apparently, the guilt for having done that turned him into a life-long protector of the studio. Another moment preserved in the studio’s apocryphal mythology comes with the emergency relocation from Aviatorilor Blvd. to a new office on… Alexandru Sahia St. (the future Jean Louis Calderon St.), allegedly after the studio’s dog barked too aggressively at Constantin Dăscălescu (RSR State Council member, 1972-1975; Prime Minister, 1982-1989), who was visiting the studio for a screening.

pe când Sahia era o familie”,

spun cei angajați cîndva în studio, iar poveștile lor, auzite astăzi, creează senzația unei voioase precarități colective care însoțeste viața cotidiană a acestui studio perceput ca spațiu semi-privat, asemănător coloniilor de șantier și căminelor de nefamiliști pe care documentaristii le vizitează tot mai frecvent pe traseul dintre primul și ultimul său deceniu de existență.

Asimilarea etosului studioului cu cel al unei unități familiale, identificarea Sahiei cu un alt fel de ‘acasă’ populat de familia profesională, e semnificativă în perspectivă istorică: familia şi rudenia au funcţionat că structuri de rezistenţă în perioada comunistă, oferind un spațiu esențial de retragere dintr-o lume aflată sub presiunea politicului.

Pe parcursul anilor, Sahia devine o familie care merge dincolo de metafora instituției-familie, încorporind tot mai multe familii reale, unele dintre ele pre-existente afilierii la studio, altele constituite ulterior prin angajarea partenerilor sau a progeniturilor celor deja angajați în studio – unii dintre ei la fel de talentați precum părinții lor, alții doar în căutarea unui loc confortabil, ferit de intemperiile specifice epocii (vezi, în anii 80, presiunea repartiţiilor universitare în provincie).

recall past employees. But their stories, heard today, create the feeling of a collective, joyful precarity which came with the daily life of this studio, seen as a partially private space, like the work colonies and single-living housing projects ever more frequently visited by the documentarists as they approached the final decade of the communist regime.

The assimilation of the studio’s ethos with that of the family unit and the perception of Sahia as a big family made up of many smaller families is significant in the historical context: family and kinship functioned as protective structures in the communist period, offering an essential retreat from a world under political pressure.

Pe parcursul anilor, Sahia devine o familie care merge dincolo de metafora instituției-familie, încorporind tot mai multe familii reale, unele dintre ele pre-existente afilierii la studio, altele constituite ulterior prin angajarea partenerilor sau a progeniturilor celor deja angajați în studio – unii dintre ei la fel de talentați precum părinții lor, alții doar în căutarea unui loc confortabil, ferit de intemperiile specifice epocii (vezi, în anii 80, presiunea repartiţiilor universitare în provincie).

Pe lîngă copiii care, la maturitate, devin ei înşişi documentarişti sau ocupă poziţii auxiliare în studio – ca portari, monteuze, proiecţionişti – cresc și alți copii care se joacă în grădina sau pe coridoarele studioului, participa la petrecerea de Anul Nou (Crăciunul e interzis), iar odată ajunşi la maturitate, în afară studioului, rămîn cu nostalgia Sahiei ca spațiu al copilăriei.

Vizionate azi de cei care au fost cândva obișnuiți ai locului, unele dintre filmele studiouluicinematograf stârnesc ocazional exclamaţii de surpriză la vederea unui copil sau a altuia care traversează cadrul, culege trandafiri sau cară un acumulator într-un film sau altul: Ia uite, aici nu e nepotul lui Mirel Ilieşiu? Aici nu-i cumva fiica Segallilor ?

În amintirea celor din urmă, Sahia rămîne o instituţie controversată, cu credibilitate limitată, care le-a rămas în memorie din anii 70-80, cînd proiecția în cinema a filmelor de ficțiune era inevitabil deschisă de o „completare” Sahia – de cele mai multe ori, una cu temă politică.

From the children born to film-maker couples, many came themselves to work at the studio: some as talented as their parents, others just looking for a comfortable position, sheltered from the harsh political climate of the period. Others who grew up while playing in the studio’s garden or under the editing tables, and who enjoyed the annual New Year parties at Sahia, remain nostalgic for it as the space of their childhood.

Seen today by those once intimate with the life of the studio, some of the films produced in the studio bring about gasps of surprise at the sight of one child or other who passes through the frame or appears in a sequence picking flowers or carrying a battery for the film camera: Look, isn’t that Ioana, the Holbans’ daughter? Isn’t that boy Mirel Ilesiu’s nephew? Look, that’s the Segalls’daughter!

In the memory of the latter group, Sahia’s reputation as a discredited, controversial institution carries over from the memory of the ‘70s and ‘80s, when screenings of fictional films inevitably began with a “support” film from Sahia— and one with an agenda.

La sfârşitul anilor 70, Paula şi Doru Segall, regizoare și operator, se pregătesc să-i filmeze pe elevii clasei a VI-a a Liceului „Ion Creangă” din Bucureşti. Cînd regizoarea le cere elevilor o definiție ad-hoc a filmului documentar, o elevă răspunde disciplinat – iar răspunsul e inclus în filmul Ședință cu părinții –

Towards the end of the ‘70s, film-maker Paula Segall and cinematographer Doru Segall were preparing to film 6th grade students at a school in Bucharest. When the director asked the students for a definition of documentary film on the spot, a girl responded promptly – and the response was included in the film Parents Meeting –

Secvența concentrează motivul frustrării de decenii a documentariştilor: anume, documentarul înţeles ca „film care se dă înaintea Filmului” – adică, în jargonul epocii, un film „de completare,” veşnic dependent de lung-metrajul de ficţiune care face regulile în cinema. Modelul de distribuție în cinematografe face că documentarul să fie înghesuit în segmentul de timp limitat de la începutul filmului de lung-metraj, rezervat azi reclamelor. Din acest motiv, majoriatea filmelor produse de studio – în special în anii ‘70-‘80 – trebuie să se încadreze în durata standard de zece minute, cu ocazionale extensii pînă la douăzeci de minute. Însă această durată poate fi extinsă substantial în cazul filmelor de comandă politică, cărora li se permite să ruleze independent, în absența ficțiunii de lung-metraj.

This anecdote reflects the decades-long frustration of the Sahia film-makers: the documentary understood as a “film shown before the (main) films”, or, in the parlance of the times, a “support” film which always depended on the feature film which dictated the rules at the cinema. The cinema distribution model of the time squeezed documentaries into a limited time-slot before the beginning of the feature films, which today is filled with advertisements. For this reason, the majority of films produced by the studio—especially in the ‘70s and ‘80s—needed to fit the standard time of ten minutes, with occasional extensions of up to twenty minutes. That time limit could be considerably extended, however, for politically commissioned films which could even be screened independently, unattached to any fiction film.

Majoritatea documentariștilor aspiră profesional la un documentar conceput şi distribuit în proiecţie independentă, eliberat de obligaţia ataşamentului faţă de ficţiune, dar și de presiunea tematicii politice. Într-un interviu din anii 2000, Doru Segall declară că statutul documentarului că film fără drepturi depline îi aminteşte de modul în care e perceput uneori copilul, ca adult imperfect – o afirmație probată de traseul ulterior al documentarului românesc în post-comunism: conform legislației cinematografice în vigoare, în România, filmul documentar dobîndește drepturi depline ca producție de lung-metraj abia către mijlocul anilor 2000.

The majority of documentarists professionally aspired to a documentary conceived and distributed as an independent screening, free of the obligation to appear alongside a fictional film, and free of the pressure of a political agenda. In an interview in the 2000s, Doru Segall declared that the documentary as a film without the right to an independent existence was akin to the way in which children were regarded as incomplete adults. His assertion was probed later in the post-communist years: Romania’s cinema legislation allowed documentary film to acquire full rights as a feature-length production only around the mid-2000s.

Ziua de muncă la noi începe de dimineață. În colonie, şoferii care transportă muncitorii încep la trei, cei care fac naveta, încep la patru, ceilalţi la cinci. (Cota Zero, L. Damian, 1988)

Venea directorul pe la nouă-zece şi zicea, vreau să-l văd pe regizorul Cutare. Eu nici nu era nevoie să mă uit, că ştiam că n-a venit încă. Îi ziceam de la început: e devreme, tovarăşu’ director, n-a venit, încercaţi mai târziu. Pe la unu jumate îşi amintea din nou. Mă duceam, verificam, mă întorceam şi-i spuneam: e prea târziu, tovarăşu’ director, regizorii au plecat deja.(interviu cu o fostă angajată a studioului)

Our workday starts early in the morning. On site, the drivers who transport the workers begin at three, those who are shuttled in begin at four, and the others at five. (Elevation Zero, L. Damian, 1988)

The director would come around nine-ten and would say: I want to see filmmaker So-and-So. I wouldn’t even need to look as I already knew he hadn’t come yet. I would answer: it’s early, comrade director, he isn’t here, try later. Around one thirty he would remember and call again. I would go, check, and came disappointed: it’s too late, comrade director, all the filmmakers left already.

Cînd, unde, cît și pe cine filmează documentaristii României socialiste?

Who, where, and for how long do the documentarists of Socialist Romania film?

Munca documentariştilor e mulată pe modelul oficial al muncii în socialism. Sunt angajați cu normă întreagă – spre deosebire de colegii de la studioul de film de ficțiune „București” (Buftea), care, după anul 1970, lucrează „pe contract”. Activitatea studioului de film documentar e asimilată producţiei industriale: Sahia e frecvent descrisă ca o „fabrică de realitate”, unde documentaristii lucrează „la foc continuu.”

În special după „tezele” din iulie 1971, munca documentariştilor începe să fie definită de o normă de filme care trebuie realizată anual de fiecare dintre ei, şi de cota de pelicula alocată per film. În vreme ce angajații studioului notează cu îngrijorare redogmatizarea producţiei, studioul e elogiat pentru reuşite exprimate cantitativ: un articol din Contemporanul intitulat „Filmul documentar şi ritmurile României” notează faptul că în cel de-al douăzeci şi cincilea an al Republicii Socialiste România, Sahia a produs 170 de documentare pe an, ceea ce înseamnă aproximativ un film de scurt metraj la două zile. Cultura de producţie a studioului e consubstanţială celorlalte industrii socialiste: un raport intern produs la începutul anilor 80 notează „tendinţa de asimilare mecanică a producţiei de film cu producţia materială bazată pe sterotipizare, sporirea necontenită a normelor şi absolutizarea cantităţii”. Nu întâmplător, cînd Ada Pistiner realizează un film despre calitatea precară a mai multor industrii ale momentului (Răspunderea pentru calitate) include producția de film documentar printre ele.

The work of the documentary film-makers was shaped after the official model of work in socialism. They were full-time employees, unlike their counterparts at the “București” (Buftea) fiction film studio who, after 1970, were permitted to work freelance. The activity of the studio was routinely assimilated with industrial production: “Sahia—the reality factory” and “Sahia—24 hour production” were just two of the slogans associated with it.

The so-called ‘July Theses’ (the name given to a speech delivered by President Nicolae Ceaușescu in 1971) marked the beginning of a period of re-dogmatisation after the modest liberalisation of the 1960s and a turning point for documentary practice. Around the mid-1970s, the work of documentary filmmakers started to revolve around the annual quota of films assigned to each filmmaker and the quota of film stock allocated per film. While filmmakers experienced a gradual tightening of the ideological control, the studio was praised in the press for achievements that were often expressed in quantitative terms: an article in the Contemporanul weekly remarked that ‘in the twenty-fifth year of the Socialist Republic of Romania, the Sahia studio produced one hundred and seventy documentaries, which means approximately one short film every two days’. The production culture of the studio was seen in the same light as that of the country’s other industries. An internal report produced at Sahia in the early 1980s stressed the “emphasis placed on quantity”, the “tendency to assimilate film production mechanically with other types of material production”, which resulted in a ‘steady increase in film quotas’. When film-maker Ada Pistiner investigated the poor quality of a series of industrial products, it was no coincidence that she included documentary production among them (see Quality Control).

Munca ocupă un loc central în imaginarul României socialiste și dezvoltă o familie semantică dramatizată constant de filmele Sahia: muncă-alienantă vs. muncă-eliberatoare, muncă vs. refuz al muncii, muncă-proces şi produs al muncii, muncă în timp, spaţii ale muncii, muncă feminină emancipatoare, şi lista poate continua. Muncitorii și documentariștii circulă umăr la umăr. Conform discursului oficial, muncitorii sunt piese indispensabile ale angrenajului social - clasa conducătoare, conştientã de rolul sãu istoric. Documentaristii – descriși frecvent în documentele oficiale că „lucrători din cinematografie” – sunt mandataţi să reprezinte „realitatea vie” a muncii primilor. O vor face vreme de decenii, până la saturare. În primul deceniu post-comunist, realitatea dură a industriilor în colaps ale României va rămîne ne-documetată în cinema pentru că documentaristii experimentați, care vin cu experiența Sahia, vor evita spațiile industriale, cîndva obligatorii, ale documentarului (cu o expresie a anilor 90) „de tristă amintire.”

În 1964, cînd operatorul Doru Segall obţine un Porumbel de argint la Festivalul de la Leipzig – pentru Marile emoţii mici, în care filmează copii în prima zi de şcoală – e criticat la nivel oficial pentru „cantonarea în teme facile” şi sfătuit să se îndrepte spre temele mai „fierbinţi” ale prezentului. Întrebat de revista Cinema ce crede că-i lipseşte documentarului Sahia, Segall răspunde că ar trebui făcute mai multe filme care să fie într-adevăr într-adevăr documente despre oameni, cu oameni, cu oameni precişi […] Filmăm bine şantierele, de pildă, dar imaginile noastre pe bene şi macarale nu duc în adânc. Ajungem în imagini standard, foarte frumoase, dar standard. Ce se întâmplă cu constructorii aceştia după muncă? Ce fac cu timpul liber acolo, pe şantier? Ce fac femeile lor? Cum îi aşteaptă, cum trăiesc aceste familii? Aparatele noastre tac. Aparatele tac pentru că li se cere să tacă. Ca observatori profesionişti, documentariştii ştiu întotdeauna mai mult decât pot să spună, identifică acut paradoxurile lumii în care trăiesc. Însă cunoaşterea acumulată poate fi doar parţial filtrată în substanța filmelor. În timp, frustrarea devine un element constant al practicii documentare.

Work was a central feature in Socialist Romania’s imagination. The films produced at Sahia revolved around the semantic family of work: work construed as alienating or liberating, work that is full-time, salaried, fervent, exuberant, work as a process, work in its temporal dimension, gendered work, and the list goes on. Workers and documentarists walked side by side. They shared an onerous position assigned to them as part of the official discourse of the one-party state: the workers were indispensable pieces in the gears of society, the leading class, conscious of its historical role, on behalf of which the Party ruled; the documentary filmmakers also enjoyed the official limelight, being that privileged category of cinema workers tasked with depicting the country’s revolutionary present and, not least, the workers themselves. And for decades that was what they did, even to excess. In the decade immediately following communism, the harsh reality of Romania’s industrial collapse went largely unaccounted for in in the documentary form, since film-makers, jaded after spending four decades in the company of the working class, shunned the collapsing factories of post-communist Romania.

In 1964, when cinematographer Doru Segall was awarded a Silver Dove for The Biggest of the Small Emotions (1964), a film about children during their first day at school—he was criticised for “taking shelter in light topics” and advised to re-orient his practice towards the major themes of the revolutionary present. When Cinema monthly asked him what could be done to improve domestic documentaries, he replied that documentary filmmakers should shoot more investigative documentaries and more films that were documents ‘about people’: We are good at filming work sites, but the images we film from cranes don’t cut to the core. We get to standard images, very beautiful, but standard. What happens to these construction workers after work? What do they do with their free time there on site? How are their families? Are they waiting for him? What are the lives of these families like? Our cameras are silent.

But the cameras were silent because they had to be. As professional observers, the filmmakers always knew more than they could put into their films. They were always aware of the paradoxes of the world they inhabited. Yet this accumulated knowledge could only be partially distilled into their films. Over time, frustration became a regular feature of documentary practice.

Producţia de film se face pe baza unui Plan tematic anual, aprobat în anul precedent de o comisie externă studioului, care urmărește alinierea proiectelor de film la conținutul celor mai recente documente de partid. Pentru obținerea aprobării pentru intrarea în producție, textura cotidiană și asperităţile realului trebuie înghesuite în geometria ideologică simplistă a „Planului.” Paradoxal însă pentru o instituție identificată cu privirea oficială a statului socialist, Sahia oferă – în interiorul industriei de film naționale – un cadru instituțional mai puțin controlat decît cel al studioului de cinema de ficțiune unde, în special în anii 80, verificarea ideologică a filmelor se face prin confruntarea filmului cu scenariul dactilografiat și aprobat cu ștampila pe fiecare pagină. Astăzi, mulți dintre foștii angajați ai studioului Sahia insistă că gradele de libertate de care s-au bucurat cîndva s-a datorat în mare parte celor două persoane aflate la conducerea politică, respectiv administrativă, a studioului: secretarul de partid Virgil Calotescu și directorul studioului, Aristid Moldovan – ambii funcționând, pe baza unor strategii diferite, ca scuturi umane ale studioului și angajaților.

Films were produced according to an annual Thematic Plan aligned with the content of the most recent Party documents and approved by a commission external to the studio.. To be approved for production, the coarseness of the real needed to fit with the simplistic ideology of “the plan”. Yet paradoxically for an institution regarded as the Party mouthpiece, Sahia offered a less controlling institutional framework than that of the fiction film studio where, especially in the ‘80s, the films were ideologically vetted by checking them against the approved scripts. Today, many of the former employees of the studio insist that the extra-freedom they enjoyed was due in large part to two people in the studio’s political leadership and administration, party secretary Virgil Calotescu and studio director Aristid Moldovan, both operating as human shields for the institution and its employees.

Să spunem de la bun început: studioul nu e un câmp de bătălie unde regizori virtuoşi luptă neabătut împotriva Statului inflexibil. Nu e nici instituția blamabilă populată de regizori-„propagandiști” .

To be clear: the studio wasn’t a battlefield where virtuous film-makers fought tirelessly against the State, nor was a reprehensible institution populated by “propagandists”.

Privind înapoi spre studio – și, în bună măsură, spre experiență socialismului trăit – intrăm în zona gri a memoriei, dincolo de perspectiva în alb/negru cu care am fost socializați în ultimele trei decenii. În interstițiile binomului dizidență/colaborare, atît de des invocate, există o multitudine de opțiuni intermediare pe care indivizii și comunitatea la experimentează diferit de la o persoană la alta și de la perioadă la alta. Vreme de patru decenii, comunitatea Sahia internalizează restricţiile şi adaptează regulile, testând diverse forme de poziționare în relație cu puterea politică: ataşament, compromis, acomodare, conformism, colaborare, supravieţuire, alienare. Negocierile se fac diferit de la un practician la altul. Soluțiile sunt invariabil individuale – inclusiv aceea de a „rămîne în străinătate” (expresia încetățenită în epocă – pentru că, din România comunistă rar „pleci” pur și simplu; de cele mai multe ori ajungi, printr-un noroc, undeva, să zicem la un festival de film, și decizi că ți-ar fi mai bine dacă ai rămîne acolo).

În special în ultimul deceniu al regimului Ceaușescu, practica documentară devine pentru mulți o formă de discretă de acomodare, echivalent al cunoscutului „noi ne facem că muncim, ei se fac că ne plătesc“ propriu epocii. Nenumărate producţii rutiniere îngroaşă filmografia politic corectă a studioului, asigurând continuitatea instituției și, în unele cazuri, traiul ceva mai confortabil al autorilor. Există totuși o anume distribuție a responsabilităţilor în studio, unde un număr relativ mic de regizori (Virgil Calotescu, Pantelie Tuţuleasa, Ion Visu, David Reu, plus alţii mai puţîn semnificativi) acoperă, în procente diferite, producţia politică obligatorie a studioului, construind o faţadă la adăpostul căreia ceilalţi regizori fac filme în care își modelează estetica sau bifează producţii rutinere.

Looking back at Sahia and, in general, at the lived experience of socialism, we arrive at a grey area of memory, beyond the black and white perspective that we’ve got used to in the last three decades. In the space between the frequently invoked dissidence/complicity dichotomy lay a multitude of in-between choices made by individuals and the community, varying from one person to the next, from one period to another. For four decades, the Sahia community both internalized and bended the rules, while the relationships developed by its professionals with the political power system and with their own practice varied widely: from attachment to alienation, and from enthusiasm to survival. . The negotiation was carried out differently from one individual to the next. The solutions were invariably individual, including that of “staying abroad” (an expression which took root in the period as, in communist Romania, you could rarely just “leave” but, if you went somewhere—usually by chance—you could find it more convenient to stay). /p>

Over the years, numerous studio employees decided to “stay” in different parts of the world. Others left the country legally—some of them to Israel on the basis of Jewish ethnicity, often unrecognizable under names which were Romanianized for better integration into the majority community.

For many, documentary practice became a discrete form of political accommodation, especially during the last decade of the Ceaușescu regime. Countless instructional productions were pumped into the studio’s politically correct filmography, assuring the institution’s continuity and, in some cases, a more comfortable life for the film-makers. Still, there was a fairly clear distribution of responsibilities in the studio, in which relatively few directors (Virgil Calotescu, Pantelie Tuțuleasa, Ion Visu, David Reu, and other less prolific ones) were responsible for the required political production of the studio, thus building a façade to the shelter wherein the other directors could make films which honed their aesthetics, or could indulge in routine commissioned productions.

Astăzi, narațiunea favorită a multor foști angajați cu privire la funcționarea studioului Sahia menționează aşa-zisul „sacrificiu” al realizatorilor de producţie triummfalist-politică pentru binele colegilor din studio. Însă acest sacrificiu e un teritoriu disputat pentru cei care vin cu experiența trăită a epocii – în studio sau, în general, în România.

Sergiu Huzum (și la fel cu el mulți alții, contemporani cu noi) consideră acest tip de narațiune scandaloasă prin lipsa de acurateţe istorică, așa că include în volumul său de memorii o notă cu privire la privilegiile membrilor grupului de „Protocol” de la Sahia: două costume de stofă englezească pe an, însoţite de pantofi şi butoni, gratificaţii lunare, premii rezervate filmelor politice în toate competiţiile naţionale. Totuşi, pentru profesionistul de cinema care e Huzum, frustarea e dată nu de detaliile materiale de tipul celor de mai sus, ci de tehnologia de ultimă oră la care cei de la „Protocol” au acces, în vreme ce operatorii de la grupa „Documentar” (unde lucrează şi Huzum pînă în anii 70) trebuie să negocieze la sînge calitatea şi cantitatea materialelor disponibile.

Din perspectiva istoriei de film, aceste practici ne lasă cu cîteva sute de „premii speciale,” „diplome de onoare” sau „premii pentru reportaj” acordate unor filme cu titluri precum Timp eroic pe plaiuri de legendă, O viaţă închinată fericirii poporului,Solie de pace și prietenie în țările socialiste din Asia.

Today, one of the mythologies of the studio is the willing ‘sacrifice’ made by the film-makers involved in politically triumphalist productions allegedly for the sake of their peers.Yet, for those with lived experience of the period—in the studio or in Romania, in general—this sacrifice is an uncertain claim.

Cinematographer Sergiu Huzum and many others with him consider this kind of narrative outrageous for its historical inaccuracy. After hearing a former colleague speak about the sacrifice of the political filmmakers from the studio’s “Protocol” department, Huuzum included a note in his memoir about the privileges reserved for the ‘Protocol’ professionals. Amongst the privileges listed by Huzum were two English tweed suits per year, together with shoes and cufflinks, hefty monthly bonuses and, not least, prestigious awards set aside for their films in all the main national competitions. But for a film professional such as Huzum, most frustrating of all was that the “Protocol” crews had access to top technology and film stock, while their peers not involved in political productions, like Huzum himself, had to make do with mediocre equipment and poor-quality film stock.

In film history perspective, these practices left us with hundreds of “special prizes”, “honorary mentions” or “prizes for reportage” given to films with such titles as Heroic Days in the Land of Legends, A Life Dedicated to the Joy of the People, or Mission Peace-Keeping and Friendship in the Socialist Countries of Asia.

Și-atunci, cum să privim azi către această instituție? Concentrându-ne asupra studioului „de propagandă” sau asupra instituției-familie și „oază de umanitate”? Vestea bună e că nu trebuie să alegem. Dincolo de alb/negru, există întotdeauna opţiunea mai sănătoasă de a încerca să înţelegem acest studio în termenii unui spectru de comportamente și decizii individuale care sunt, dealtfel, vizibile și la nivelul producției. Studioul Sahia pe care îl propunem aici este, deopotrivă, casă a unora și instituție de propagandă a altora, familie şi fabrică de realitați pre-scrise politic. Ambiguitatea, contradicția, paradoxul sunt esențiale pentru a schița portretul acestei instituții populate deopotrivă de profesionişti impecabili, oportunişti blazaţi și politruci generoşi.

And how should we judge the remains of this institution today? With a focus on the propaganda studio or the homely institution, the oasis of humanity? The good news is that we don’t have to choose. Going beyond the black and white, there are always healthier ways of coming to an understanding of this studio, in terms of a spectrum of individual behavior and decision-making which can be understood in more than one way. The Sahia studio that we choose to present here presented is a home for some and a propaganda institution for others, and at times both a family and a factory of politically prescribed realities. Ambiguity and contradiction are essential to outline the shape of this paradoxical institution populated by impeccable professionals, as well as blasé opportunists and generous apparatchiks.

La trei decenii de la colapsul regimului Ceaușescu, încercăm o poziție echidistantă, mergând dincolo de eticheta de „studio de propagandă” și menținând distanța față de nostalgiile celor afiliați cândva studioului. Nu e posibil un verdict clar cu privire la trecutul studioului Sahia, așa cum e imposibil de construit o poveste unică în jurul socialismului trăit în România epocii.

Three decades from the collapse of the Ceaușescu regime, we are trying to find a middle ground, steering clear of the label of “propaganda studio” and stopping short of the nostalgia held by those once affiliated with it. It is impossible to arrive at a clear verdict concerning Sahia’s past, just as it is impossible to tell an essential story covering the lived experience of socialism in Romania.